The million-dollar question for managers: How do I motivate my employees and keep them motivated?

Over 20 years I’ve managed individual employees and built high performing teams, and I’ve always been perplexed by the large disparity in performance between equally skilled individuals. Figuring out why has become my life’s work.

My investigation led me to the work of Sigmund Freud, who borrowed the term “dynamics” from physics when he coined “psychodynamics”. We can further apply the logic of physics to the understanding of work motivation, which I define as the desire to exert effort toward completing job tasks.

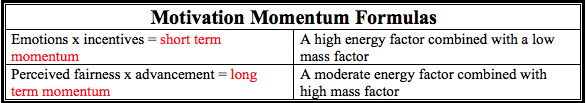

I take this a step further and introduce the term motivation momentum as a psychological combination of mass and velocity (mass x velocity = momentum). Often we hear a sportscaster describe a team as having momentum, and we might ask: What factors contribute to that kind of momentum? How does it work? Just as Freud suggested, the problem is dynamic in nature.

One of the key factors in motivation momentum lies along the following continuum:

“Why should I bother doing this?” “Why it is I really want to do this?

Employees that sustain high performance levels tend to have reasons behind their desire to work hard.

Conversely, low performers tend to have reasons that leave them wondering why should they bother.

Examples of these mass variables include pay, working conditions, benefits, achievement, growth, and advancement. Examples of these velocity factors include emotions, perceived fairness, self-concept, and social perception.

What gives these factors mass is how much or deep they can impact an individual’s psyche. I also call these nurturing and non-nurturing factors. Nurturing factors are factors such as achievement, growth, and advancement. These factors are developmental and can possess great amounts of psychological mass. Whereas, pay, working conditions, and benefits are non-nurturing factors, are not typically used for developing employees, and possess less psychological mass.

Subsequently, velocity factors are the individual differences of each employee that fluctuate, and are more or less stable. For example, moods and emotions can be intense and change rapidly, generating large amounts of energy and creating short bursts of psychological velocity. Factors like perceived fairness are more stable, and provide less of a spike in energy, but have a greater impact on the long-term trajectory.

The combination of how these mass and velocity factors interact produces varying degrees of motivation momentum. Understanding the mechanics that create motivation momentum can be an essential tool for managers. Depending on the immediate or long term goals of an organization, managers can adjust their approach to motivate their employees.

Such as, a sales manager may target the moods and emotions of each team member to elicit a quick burst of motivation momentum to achieve an immediate goal. Conversely, a manager seeking long-term motivation for a project team may target the more stable factors such as perceived fairness and social perception to elicit motivation momentum that has more staying power.

Human capital is the most important resource of any organization, and motivation momentum can empower individual achievement, attain organizational objectives, and increase the bottom line. This is one of the most important challenges organizations face. We can brainstorm strategy until we are blue in the face, but if our employees are not inspired to see it through none of it matters.